For an incredibly brief period in the 1950’s, Ireland produced a car. More accurately, an American business man planned to mass produce an executive car in Ireland for the US market. This is a big deal, yet it’s something that’s largely forgotten. Its thought only 10 were ever produced, and only 8 are known to survive.

The Shamrock is an incredibly rare car. So rare that both my parents who grew up in Ireland never heard of it. The first exposure any of us had was when Top Gear did a quick little feature of it in 2001.

The idea to produce an executive luxury car for the American market began with William Curtis. He was an American industrialist, and had wanted to start producing cars in Ireland for export to the USA. The story goes that Curtis was visiting family in Ireland. While he was there he couldn’t believe the levels of poverty and unemployment in the country.

So he decided that, logically, he should design and build a car in Ireland to then sell in America. Because that’s the sort of thing you do when you’re on holiday. To understand his reasoning, you first have to understand what Ireland was during this time.

A very brief history lesson

Ireland, during the 1950’s, wasn’t exactly in great shape. She had just became a republic in 1949, terminating her membership of the British commonwealth. That came after a period of civil war. Ireland had only recently joined the United Nations during the mid-1950’s, even after continual vetos from the Soviet Union.

Her economy wasn’t great, primarily agricultural in its nature with little to no manufacturing. The Irish continued to emigrate, primarily to the UK and to the USA to look for work in order to survive.

So your an industrialist with an idea to make a large amount of cars. It makes total sense to choose a location where land is cheap and there’s a supply of labour. John DeLorean had a similar idea in the late 1970’s/early 1980’s. Except with Shamrock, the state didn’t provide financial assistance. None that I can see from my research anyway. Plus cocaine wasn’t as lucrative in the mid-1950’s as it was when DeLorean was looking for a cash injection.

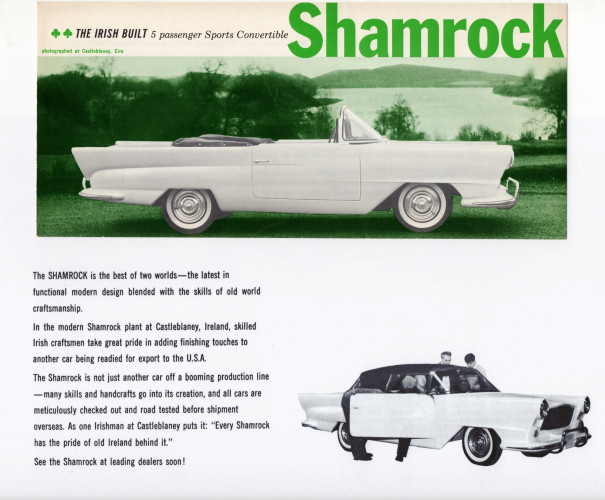

Curtis was joined by another American businessman called James Conway, and together they founded the Shamrock Motors Ltd company. The company had originally intended to build the cars in Tralee in County Kerry. But it’s thought that this became problematic, and operations were quickly moved to Castleblayney in County Monaghan.

A car is designed, but not thought out

Shamrock Motors Ltd now have the location to build their executive car. They have a ready supply of labour in order to make it happen. But the workers can’t build something that doesn’t exist on paper. This is where we introduce another chap in to the story. A man called Alvin ‘Spike’ Rhiando.

Rhiando, by all accounts, was a proper man of mystery. An early prototype for Austin Powers maybe. During the 1930’s he made a name for himself on the speedway circuits in the UK. Promoters seemed to latch on to his exotic sounding name and promoted him as being Italian. Somehow, this Italian soon became American. And then Canadian.

Then some people who weren’t huge fans of his came out and tried to destroy this illusion. How? By calling him “a Londoner with a touch of showmanship”. He was from Deptford, apparently. However he’s definitely someone I’m going to do more research about in the future. For now, though, all you need to know is that he’s the designer of the Shamrock.

Rhiando was asked by Curtis and Conway to help design the Shamrock. Christ knows where, how or why Rhiando was asked to design the car. Or even how Rhiando came in to the equation at all. Some sources actually put the design of the Shamrock down to Curtis. So this part of the car’s genesis is quite sketchy. Whoever designed the Shamrock though, they did something spectacular. They did a really good job in providing a case study on how not to design a car.

Bigger isn’t always better

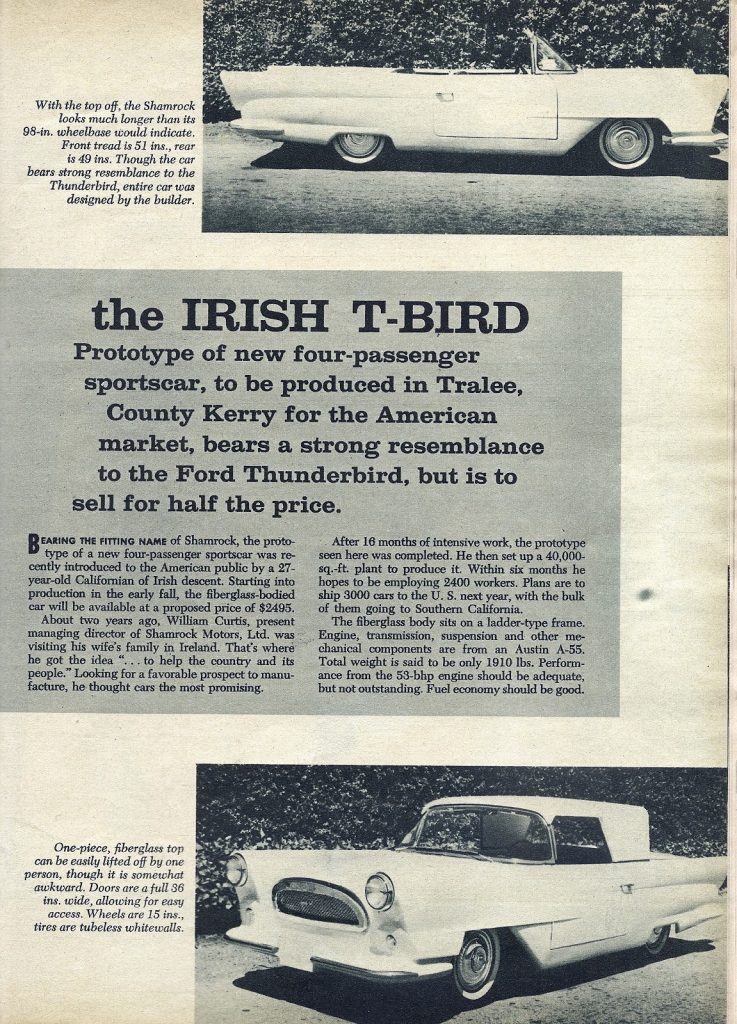

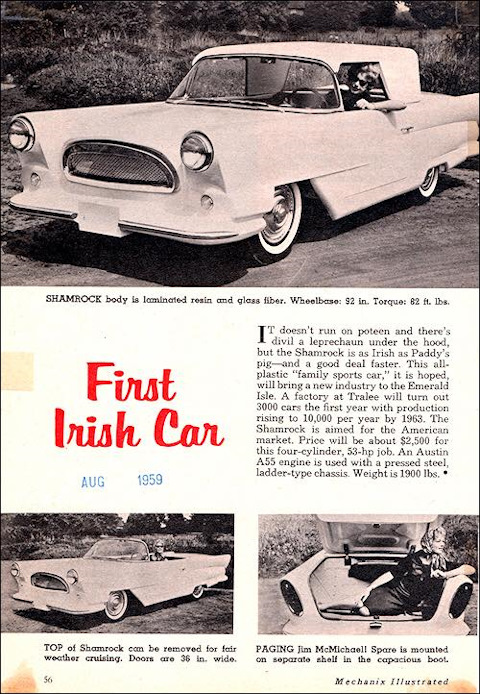

The Shamrock that was designed and produced ended up being 17ft long. In new money, that’s 5.18 metres long. This was a huge car, for a market where they liked everything bigger because everything bigger was obviously better.

While the Shamrock was bigger than most cars, it wasn’t better. The 17ft body was primarily made out of fibreglass. This was pinned on to the running gear of an Austin A55 – quite literally. The huge heft of the Shamrock, regardless of the materials used, meant that performance was poor.

The Austin A55 – or Austin Cambridge – came complete with a 1.5 litre 4-stroke engine producing around 54 bhp. The Shamrock was 5.18 metres long, and the Austin A55 was only ever 4.2 metres long. This meant that the Shamrock was effectively a 20 stone guy trying to get a 50cc moped to do 50mph.

The final quirk of the Shamrock is saved for the rear. The Shamrock’s styling is heavily influenced by American car design of the time. There is no mistake or coincidence in the fact the Shamrock’s rear quarters utilised huge fins. This was a car that was meant to make a statement to whoever saw it. This is the best example of Americana and you could be driving it. It was a car to turn heads, something to aspire to. Did you want a Thunderbird but couldn’t afford it? No worries, the Irish have built a better Thunderbird with the Shamrock.

The combination of the styling and the car’s Austin A55 underpinnings meant changing the rear tyres became such an event. It wasn’t a case of jacking the car up and taking the wheel off. No, you had to drop the whole rear axle to gain access to the wheels. Imagine doing that on a cold wet evening in California.

A Shamrock between two thorns

Once the Shamrock was unveiled, the reception to it was luke warm at best. It was unveiled to the public with a price point of a whopping $2,459 (equivalent of over $22,000 in 2019). William Curtis was quoted as saying that he hoped to be able to produce 3,000 Shamrocks in the first year. This would then be ratcheted up to produce 10,000 in the future.

One US car critic commented that the Shamrock was “like a small English car wearing a big American car costume”. Unfortunately for the Shamrock, this was a popular view point of the car. The Shamrock was far too under-powered for the American market, and it was far too large for British roads. The Shamrock was woefully inadequate for both the US and UK markets, so no one bought a single Shamrock.

With any new venture, cash is king and cash flow is the life blood of any organisation. Shamrock Motors Ltd had no life blood. In 6 months Shamrock Motors Ltd produced 10 to 50 cars before the doors closed on the Castleblayney factory. Just like that, the Shamrock was no more.

Today it’s thought that about 8 of the 10 cars are still in existence. Five of these cars are still spread throughout Ireland, with the rest found in America. Most, if not all, of the Shamrock’s built were only ever painted white. But one Shamrock can be found appearing in it’s local St.Patrick’s Day parade painted in candy green. It was painted by the owner to celebrate his own Irish heritage, after rescuing it from abandonment in Los Angeles.

The road to hell is paved with good intentions

People talk about the “luck of the Irish”. However, Ireland’s had about as much luck as the owner of a pair of brand new shoes left on the table with a black cat sitting on them. It’s a cliche that seems to be used just because it references the Irish.

An old friend of my dad’s told me about his own experience of emigrating from Ireland to work in England. He, like many others before him, would take the Princess Maude cattle ship from Dublin to Holyhead. As the ship sailed away, they would look at their home and wonder whether they’d ever see it again. Some did, but so many didn’t.

It’s a huge pity, in my opinion, that the memory of William Curtis isn’t remembered today. He had made his money in America. He was on holiday when he was inspired to help the people he saw. The people who stayed behind and did their best. He wanted to help them make more of themselves and more of their country. Curtis had no help from the Irish government of the time. It was all through his own efforts and those of James Conway. He decided to build a car in Ireland to provide employment and pride in the country of his ancestors.

The road to hell is often paved with good intentions. If there was ever a definition of that saying then the Shamrock serves as that. It’s easy to mock the car as being far too big for the local market. For being woefully under-powered for it’s target market. It’s even easier to mock the decisions that lead to a puncture repair requiring the removal of it’s rear axle. But as far as I’m concerned the Shamrock should be remembered fondly for what it tried to achieve. For that, Mr.Curtis and Mr.Conway, at least here on this small corner of the internet you’ll be remembered for trying to do the right thing.