It’s something that should be said quietly in order to not offend too many people, but F1’s last “golden age” existed between the late 80’s through to the end of the 90’s – specifically when it came to engines. There was a real selection of engines to choose from. You could go with a V8, a V10, or a V12. You could get that V8 from Ford if you were on a budget, or if you were doing really well for yourself – a V10 from Renault. You wouldn’t consider the Yamaha OX99 though, would you?

Well if you were a team that just joined the sport in 1991, you’ve just realised the cost of competing in Formula One was way more than what you thought it’d be, and your name was Eddie Jordan – then you would obviously opt for a V12 engine provided to you by Yamaha.

We’re 30 years on from Jordan’s blistering debut, where Ireland’s first (and only) F1 team made the jump from F3000. I can’t get across the actual true success Jordan had in their first season. New teams in F1, even back then, rarely survived past 2 seasons – let alone score meaningful points in their first season.

I won’t go in to how pre-qualifying works but new teams, along with teams who didn’t score points, had to compete on a Friday to be one of the 4 quickest out of this group of newbies and poor performers to have a chance at qualifying on Saturday. Even then, your position on the grid wasn’t guaranteed. So for Jordan to not only comfortably get out of pre-qualifying and qualify for the race on Sunday, but to score points fairly regularly in their debut season, was an immense achievement for the small team.

Need An Engine? Use Our Yamaha OX99!

According to Garry Anderson, who was the technical director of Jordan F1 through much of the history of the team, the cost of competing at the pinnacle of motorsport came as a complete surprise to the shrewd Eddie Jordan. The budget was blown long before the 1991 season had finished, leaving a debt with Ford which lead to the manufacturer cutting off their supply of Ford engines for 1992.

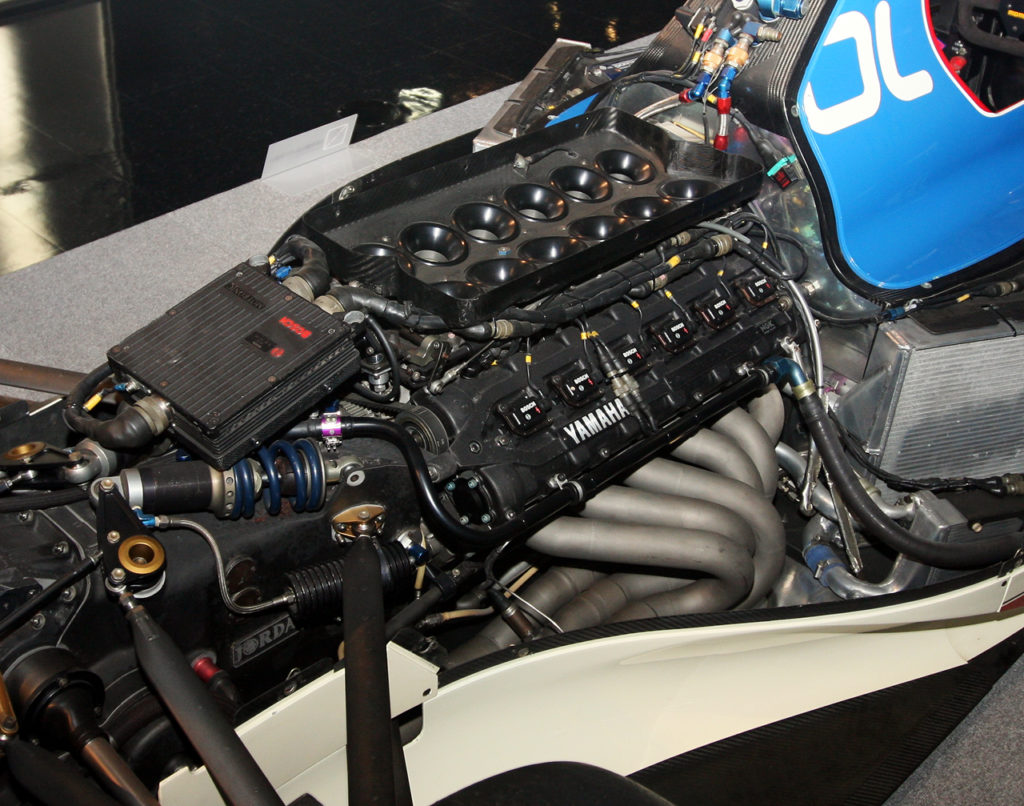

This caused problems for the team, as the 1992 car had been designed with the intention of running Ford engines – however it was a bigger problem that the car had no engine in the run up to 1992. Yamaha, however, stepped forward and offered Jordan a free supply of engines as well as a few quid. This meant Jordan could go racing in 1992, powered by Yamaha’s OX99 V12 engine.

Yamaha themselves had been involved in F1 since 1989, supplying the OX88 V12 engine to the Zakspeed team. Zakspeed only managed to get out of pre-qualifying twice in 1989, and on both grand prix’s they qualified for, retired. The Yamaha OX88 engine was their first F1 engine, configured as a 3.5 litre V8 engine. It had been thrown together using knowledge of their 2 litre OX66 V6 engine which was used in the Japanese F2 series.

This was coupled together with the 3 litre Yamaha OX77 engine – which was apparently a Ford DFV engine using Yamaha designed heads. It was regarded as heavy and under-powered, as well as unreliable. Yamaha took a year out after 1989, and came back with a big step forward in their engine offering – the Yamaha OX99.

The Yamaha OX99 was designed to address several of the problems raised from using the Yamaha OX88 – notably it’s power, strength and weight. This new Yamaha F1 engine had been intended to produce over 600bhp, and had found it’s way to powering the Brabham F1 cars in 1991. Brabham themselves were nearing the end at this point, but managed to score 3 points powered by this engine.

Yamaha themselves didn’t see a future with Brabham for a number of reasons, and found that Jordan were probably a better long term bet when it came to the further development of it’s engine and it’s F1 aspirations.

It didn’t work out. The Jordan 192 retired regularly, mostly caused by overheating and engine issues. From a recent episode of the podcast “Bring Back V10s“, Gary eluded to the issue of the Yamaha engine. He stated that (and this is paraphrased) the Yamaha OX99 was no more than an engine for use on a dyno, so the moment it was bolted on to the Jordan 192 it would vibrate itself apart. This would cause part failures, and once one part was changed another would break.

The performance just wasn’t there in race tune, and given the extra weight a V12 brings with it, the relative lack of horsepower along with the poor reliability meant there was no future for the Yamaha OX99 in F1. In 1993, Yamaha teamed up with John Judd, and effectively helped co-develop the Judd GV that powered Tyrrell for 4 years, culminating in a 2nd place at Hungary powering the Arrows of Damon Hill in 1997. Yamaha then abandoned F1 altogether that year.

The story of the Yamaha OX99 doesn’t end with the lacklustre performance of 1992. If anything, the appearance of the OX99 in F1 only serves to start the story – the OX99 was going to power Yamaha’s very own supercar – the Yamaha OX99-11.

This Poor F1 Engine Would Work Well Powering A Supercar Y’know?

Let’s go right back to 1990. As I said earlier, Yamaha had a fairly torrid first year as engine supplier to Zakspeed, only qualifying for 2 of the 16 races they entered in 1989. Yamaha had taken the decision to regroup in 1990, considering their options and settling down to design the OX99 engine, which then went on to power the Brabham.

Somewhere in this two year period, the idea started to germinate in Yamaha that they should build a road car that gave it’s driver the F1 experience and that it should be powered by the venerable OX99. You should also note as well dear reader, that during the late 1980’s the economy in Japan was fairly buoyant, so they were flush with cash and could afford to achieve such a dream.

In 1991, Yamaha appointed a company called International Auto Design, who in turn drafted in former March designer Robin Herd to oversee the design project. Robin Herd had great success in Formula One as co-founder of March engineering who had developed race winning cars for the likes of Jackie Stewart and Tyrrell, as well as providing Frank Williams with customer cars in the early 1970’s. He was also the man who helped give Adrian Newey his break in F1, as Newey started off at the March F1 team which was then sold to Leyton House in 1989.

Initially the Yamaha OX99-11 was intended to just be a single seater vehicle, but Yamaha executives were inspired by the just released McLaren F1 to have two passengers sit behind the driver in their new supercar. Helpfully, the executives had requested this after IAD spent the previous 12 months developing the prototype.

True to the initial design brief, IAD and Robin Herd had developed a chassis that had far more in common with the F1 car it was meant to emulate than the McLaren F1. It was of a monocoque design developed and fabricated entirely out of carbon fibre, which meant the Yamaha OX99 engine was mounted directly to the monocoque – just like they do with an F1 car. The bodywork itself though was all aluminium and hand built around the futuristic monocoque, which was crafted by former employees of Aston Martin. Absolutely no money was spared in the development of this supercar!

It was all shaping up to be quite a success. Having the likes of Aston Martin trained employees building the prototype cars, having a former F1 technology wizard designing the vehicle, and having a car provide the driver with a taste of F1 really meant it could’ve gone down in history as one of the all time great supercars. But by 1992, IAD – along with Robin Herd – had left the OX99-11 project over a financial dispute.

The project was handed over in it’s entirety to Ypsilon Technology – who were a subsidiary Yamaha had set up to help look after it’s F1 engines – but timescales were tight and Ypsilon Technology couldn’t achieve what was required of them in the relatively short time frame they found themselves in.

The Party Ends When The Money Runs Out

Japan was hit by a financial crisis in the early 1990’s, which only proceeded to get worse by 1992 and 1993. Supercar development costs a lot of money, especially at the final step of getting the product to market. Yamaha’s pockets weren’t as deep as they once were, and a period of consolidation and reflection occurred in Japan. Yamaha’s F1 engine division teamed up with Judd to develop their F1 engines, and Yamaha decided no one was going to pay £800,000 for their OX99-11. The plug was pulled on the supercar project, leaving only 3 prototypes ever completed. Yamaha’s supercar dream was dead, and dreams of F1 supremacy ended a few years later.

When a project is shelved by a manufacturer, two things tend to happen. The prototypes tend to be put in to storage (or destroyed) and are never seen again. Never even mentioned again. Or, the prototype serves as the basis for a new, more conservative project and prototype. Neither of these scenarios happened with the Yamaha OX99-11. Instead, Yamaha seem to embrace them, and they seem to be regularly driven at events in Japan as well as having one OX99-11 on permanent display in a Japanese museum.

A Synchronicity Of What Might Have Beens

There are stranger footnotes of F1 history that stride across in to real world motoring applications than the Yamaha OX99, but it’s said that experiences you have as a child shape you in later life. The first F1 race I ever saw was in 1996 when Damon Hill crossed the line at Suzuka to win his only championship.

I was hooked on the sport after that, and I sat there diligently in 1997 when Hill was in such control of that race in Hungary until a 50p seal on his Arrows let go. I knew the drivers of the sport, I knew the engines, and back before the internet was a thing I genuinely thought the tiny Yamaha keyboard we had in the house had absolutely nothing to do with the Yamaha that was powering the Arrows of Damon Hill!

The synchronicity of my favourite F1 driver of all time nearly win in a Yamaha powered Arrows, then going to Jordan to win their first grand prix, which gave my parents (who weren’t F1 fans at all) pride in hearing the anthem play out on the TV, mean when I heard Gary Anderson talk about Jordan and Yamaha doing something together meant it had my interest.

In the research I did after that, the idea of that F1 engine being placed in to a supercar and the possibilty of it being a little more attainable to drive than the Espace F1, meant it certaintly had my attention. I feel it’s a true “what might have been” moment, and instead of the talk of the McLaren F1 being the best supercar of the 90’s, we could’ve had the playground arguments of why the Yamaha OX99-11 was a better car than the McLaren F1.

However, it joins Yamaha’s other “what might have been” of 1997, when on the last lap that 50p seal gave out and robbed Yamaha of the closest thing to glory they ever had a chance of getting in F1.